Amazing what people invent to increase productivity and to live a healthy life. Sitting is claimed to be the new smoking today. Some of you have noticed the “movement for health” as well as did many startup projects like Locus, Big Rig, TrekDesk. They all strive to bring some solutions on the table and to capitalize on the trend. That’s good in general.

Recently I stumbled over an interesting proposal for walking while working by Robb Godshaw. Aka treadmill for humans.

Looks like a simple neat idea, let me comment and give my two cents on that.

We tend to “economize” the time: passionately texting with our smartphone while walking, reading our e-book in a backseat of a car, or reading an exciting chapter of our newly bought book when we ascend the stairs of our office. I am sure, most of the readers (including myself) did these things many times in their life. I know, eating alphabet can’t wait 🙂 I have nothing against treadmills for humans, but let’s see what happens in our brain when we move and read.

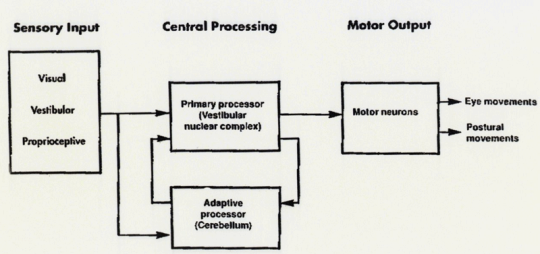

Alignment of sensory input

When we move, the brain integrates information from a variety of sources for the sake of coordination. These sources include sight, touch, sense of limb position that is called proprioception, the inner ear and, also, the brain’s own expectations. The inner ear is particularly important because it contains sensors for both angular motion (the semicircular canals) and linear motion (the otoliths). These sensors are called the vestibular system. Under most circumstances, the senses and expectations agree. When they disagree, however, conflict arises and motion sickness can occur. Motion sickness usually combines elements of spatial disorientation, nausea and vomiting.

Eye movement during reading

Eye movement during reading was described in the late 19th century by the French ophthalmologist Louis Émile Javal. There are two main types of eye movements, one is called saccades (eye movement jumps) and the other is called pursuits (smooth, tracking eye movements). Saccades are important for reading because the eyes have to jump from word to word and line to line. These are extremely small movements and therefore they have to be extremely precise in order to land the eye on the correct target. If saccades are not working in the most efficient manner possible, the eyes may seem to dart all over the place, words may jump around on the page, or a reader may skip lines. Pursuits are important for following moving targets such as in sports or when watching your hand when writing. When pursuits lack efficiency, eye/hand coordination tasks become difficult if not seemingly impossible.

Ok, now we know the basics, and you could ask “what’s next”? Now let me move ahead and talk about reading while moving.

Maintaining focus

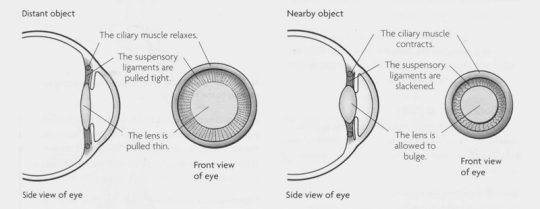

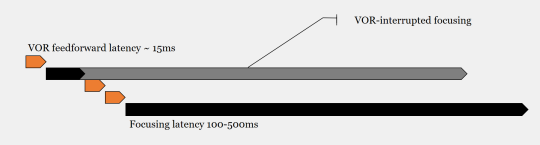

The ability of our eye to effectively change focus from distance (infinity) to short distance is called accommodation. The brain must tell the eyes to change focus rapidly for large shifts in focus distances (like from landscape to the book) or it must tell the eyes to maintain focus at short for prolonged tasks such as reading from the screen. Accommodation occurs in time range of about 350 milliseconds as a consequence of a reduction in zonular tension induced by ciliary muscle contraction. Reading highly involves focusing and it is an important visual skill that allows to maintain clear vision up close for extended periods of time. When we move, stabilization of the gaze is realized through vestibular ocular reflex (VOR) that maintains eyes relative to the external world, compensating for head movements, by rotating the eyes in opposite direction. This reflex prevents visual images from slipping on the surface of the retina (retinal slip) as head position varies. The VOR also acts during the coordinated eye-head movements (gaze shifts), compensating for the portion of the head movement that lags the more rapid displacements of the eye. VOR adaptation are controlled by the cerebellum and is driven by our built-in accelerometer, the vestibular system.

When we move, body and head position changes. Vestibular system in interplay with the cerebellum commands the gaze maintenance through vestibular reflexes. In the situation when we don’t need to maintain the prolonged close focus, accommodation just follows. As reflexes are very rapid (the latency of the VOR is about 15 ms), the focus readjustment is constantly triggered but is not necessarily complete. This happens due to the big discrepancy with accommodation latency. As a result, we could still be able to see the text but our eyes would be tiring faster.

To experience how it works in “home conditions”, just ask you friend to hold your smartphone, while you read from its screen. When your phone is in your own hand, your brain still could compensate for slight limb movement due to proprioceptive mechanisms. But this compensation becomes more and more difficult when your body movement is uncoordinated with the close target (like a text on the screen) movement/vibration. Basically, if the brain doesn’t understand where to aim the focusing system, visual stress can creep in.

So what is the point? Of course, my post is not intended to criticize inventors or scare users, but rather to increase awareness about the fact that our brain is not built to read while we move. Prolonged visual stress can cause structural changes to the eye by means of elongation of the eyeball in order to reduce the amount of focusing. As a result, long distance vision could become blurry and the person nearsighted.

What if some simple adjustments could be made to the product or to our behaviors for making us healthier at work?

Given the need of the vestibular adjustment, the designers could potentially reduce the need for the refocus by doing the following steps:

- Letting the screen move with the user’s head

- Or by tracking the head position and feeding forward the changes to constant reposition of the UI elements on the screen.

On the other hand, induced healthy behaviors would require to:

- Build environments that motivate regular periodic pauses in the daily working schedule

- Introduce physical games

- Conduct stand-up meetings

- Prioritize mental focus

- Decrease destructions and noise

Just as my wife reasonably points out to me: “one thing at a time”.